|

This virtual field trip takes us to Monument Valley, and then to a location north of there. Monument Valley is in the Navajo Nation or Dinè Bikeyah (The Land of The People). It straddles the border of Arizona and Utah, northeast of Kayenta, Arizona, and southwest of Medicine Hat, Utah.

Because Monument Valley is such a beautiful place, it's probably best to enjoy the beauty in the panaromas below before worrying about the geology. The first panorama is from John Ford Point and the second is from outside the Visitor Center. Click on each of the panoramas here to access much larger (5272 x 700 and 4616 x 700) views.

|

|

|

|

|

2636 x 350 image 5272 x 700 image

|

|

|

|

|

2308 x 350 image 4616 x 700 image

|

|

|

|

Now that you've gotten a look, we can ask the key question: what did you see?

|

|

|

|

--------------------------------

|

|

|

|

Because we're in Monuent Valley, it's tempting to say that we're looking at monuments - large hunks of stone scattered across the landscapes like statues to honor past heroes, or tombstones to honor the dead.

A closer look tells us there's more to it than that. As we scan from one "monument" to the next, we can see in each monument a sloping base of roughly uniform vertical thickness and then straightsided rock of very uniform thickness. The rock is the same in all of them, suggesting that they were all part of two (or many more) uniform layers of stone that extended across the entire region.

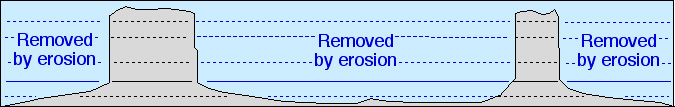

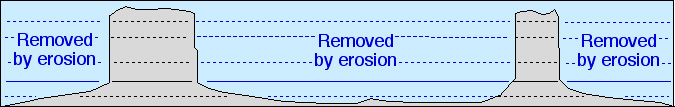

Any geologist would accept that idea of originally continuous layers. In fact, it's an easy application of Nicholas Steno's Principle of Original Conitnuity, which points out that nature would be hard-pressed to deposit sediments in layers that started, stopped, and started abruptly again. If we accept that idea of originally continuous layers here in Monument Valley, then we get to a second and even more important question: What aren't we seeing?

|

|

|

|

--------------------------------

|

|

|

|

Here's the answer: we're not seeing all the rock that has been eroded. Anyplace where can see between the monuments and to the horizion, the rock layers have been eroded away all along our line of sight. In addition, all the rock has been eroded between us and the monuments that still remain. Think about the area involved, and you realize that much more rock has been removed than remains. What's impressive is not the "monuments"; it's the volume of rock removed to leave the monuments behind.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

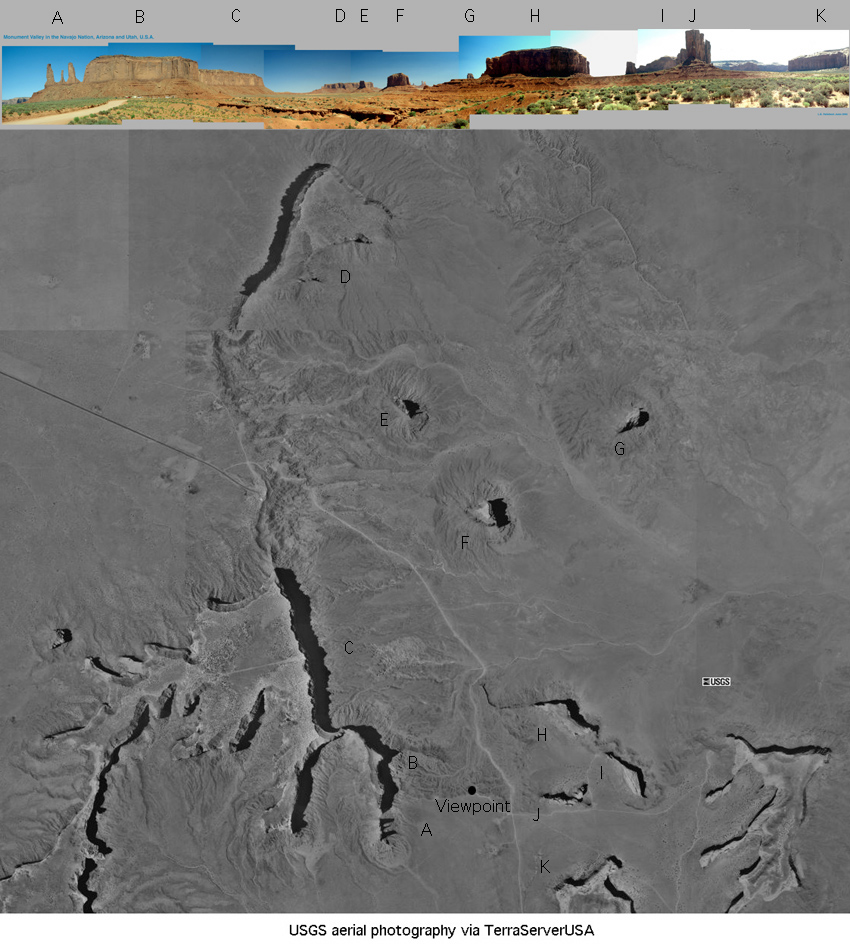

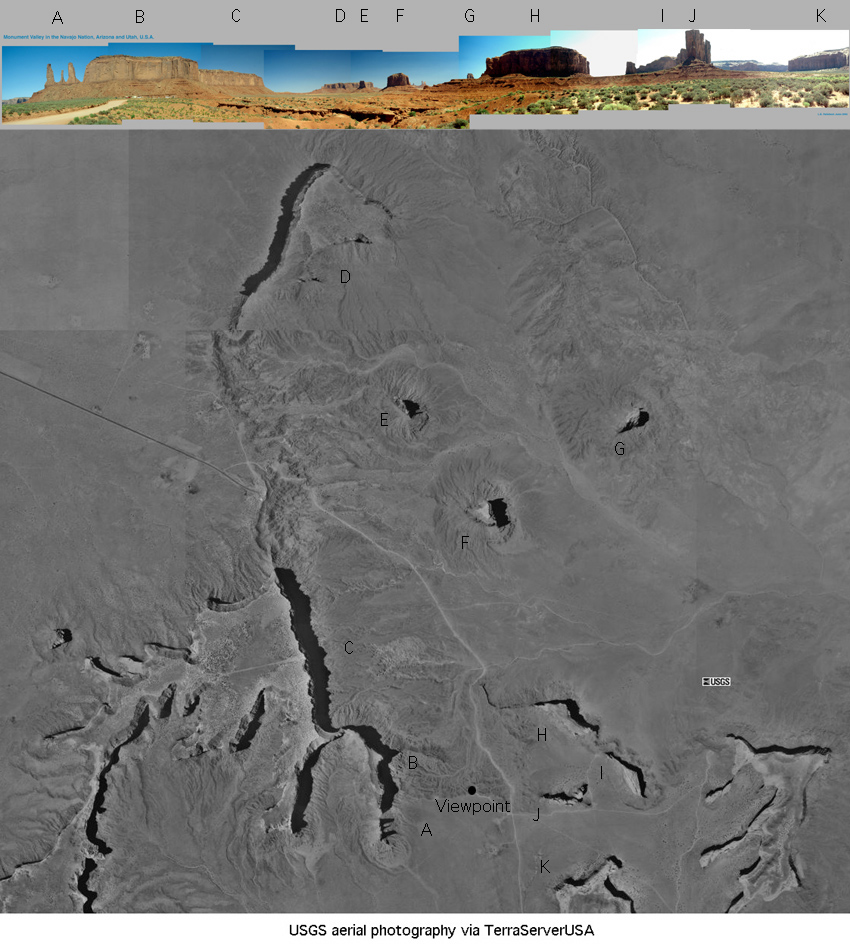

To look at things from another perspective (literally), take a look at the aerial photograph below. The mesas or "monuments" in the first panorama above are lettered below and labeled on the aerial photograph. The only word of warning is the most of the aerial photograph was photographed in the evening, with light from the west and shadows to the east, but the northernmost part was photographed in the morning, with light from the east and shadows to the west.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The conclusion from the aerial photograph is the same as from the panoramas: the rock layers visible in the mesas have been removed from a much larger area than what remains in the mesas. Our eyes focus on what is present, but the impressive feature is what's missing.

|

|

|

|

With this mind, let's go north of Monument Valley and north of Mexican Hat, Utah, and climb up the Mokee Dugway. It's a steep road cut into sandstone cliffs. When we get to the top, we're treated to a grand view as seen in this panorama. Again, click on the image to get a much larger view.

|

|

|

|

|

2336 x 350 image 4672 x 700 image

|

|

|

|

Once again, now that you've enjoyed the view, the question arises: what did you see?

|

|

|

|

--------------------------------

|

|

|

|

The view is somewhat different, in that we're standing above the eroded plain rather than on it, but the answers are much the same. We see cliffs of layered sandstone at each end of the panorama and, in between, a vast plain from which almost all those layers have been removed. Only one small pinnacle of the basal red layers remains in the center of the panorama. Again, what's impressive is what's missing: a vast volume of layered sedimentary rock has been removed by erosion.

|

|

|

|

The point of this field trip has been to prompt you to think about the amount of erosion required to produce the landscapes we're seen. Erosion is a slow process, so these landscapes should remind us about the amount of time required to produce them. The same is true elsewhere - almost any upland landscape has undergone vast times of erosion that has removed rock once present there, and the present land surface is only that: the present position of the surface cutting into the underlying. The difference is that steep landscapes like Monument Valley provide us with effective - and beautiful - reminders of the power of erosion.

|