|

This trip takes us to southwestern Utah, and specifically to a large geologic structure east of St. George and west of Hurricane. It's the Virgin Anticline, which takes its name from the nearby Virgin River.

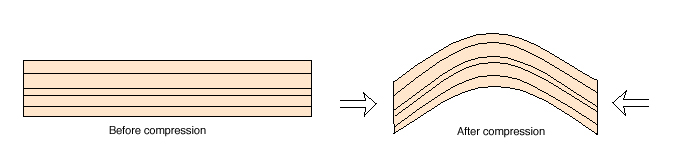

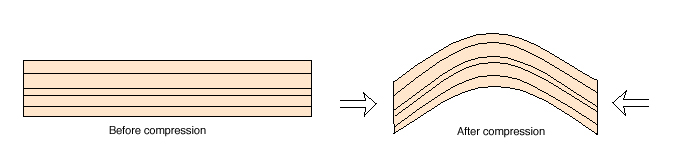

An anticline is an upward fold in layers of rock. An anticline usually forms during lateral compression. As two regions or tectonic plates are pushed toward each other, something has to give. One option is for the rocks in between to bend, just as the pages of a soft-bound book bend if we push on the binding and the side opposite the binding.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

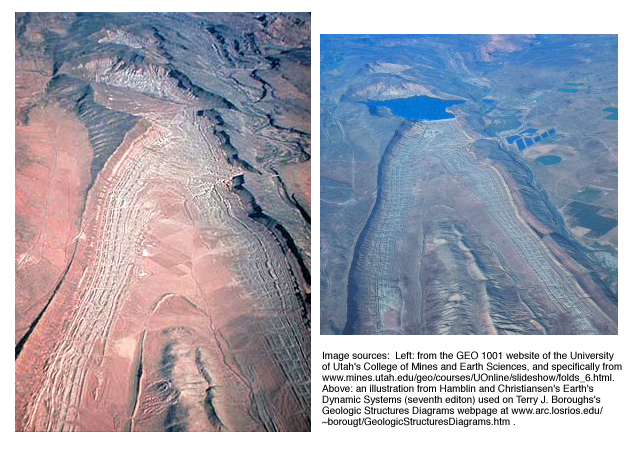

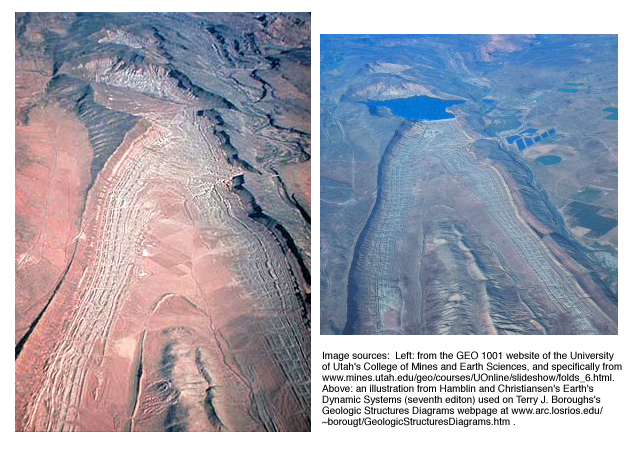

So what's the big beal with the Virgin Anticline? Well, it's big, and erosion has exposed it so that we can get a good look at it. The two aerial views below show both its size and its exposure. The picture on the left was taken before a dam was built in the north part of the anticline; the picture on the right shows the Quail Creek Reservoir dammed there today.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

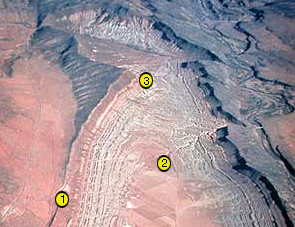

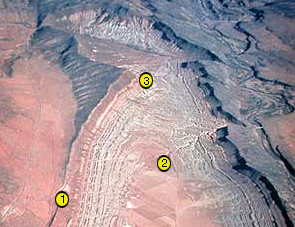

If the images from the air shown above aren't making things clear, don't worry. Our objective in this field trip is to take a look at the anticline from the ground. We'll do it from the three locations shown in yellow below. We'll be looking toward the reservoir in each.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The image below shows the view from Location 1. Click on one of the larger options to see it in all its glory. Do you see an anticline?

|

|

|

|

|

Above but 1530 x 350 pixels Above but 2928 x 574 pixels

|

|

|

|

You should be seeing an anticline. The beds to our left dip or slope away to the left. The beds to our right dip away to the right. You have to mentally connect the two with a rainbow of eroded rock to envision the anticline as it was. We've done that a little in the next image.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Let's move on to the view from Location 2. Remember that part of what we'll see in the distance is that dam, a non-natural feature.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

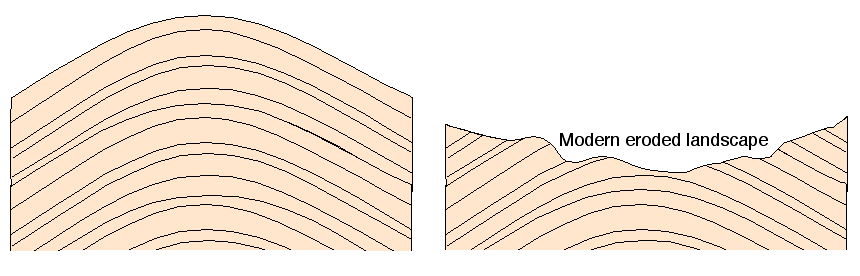

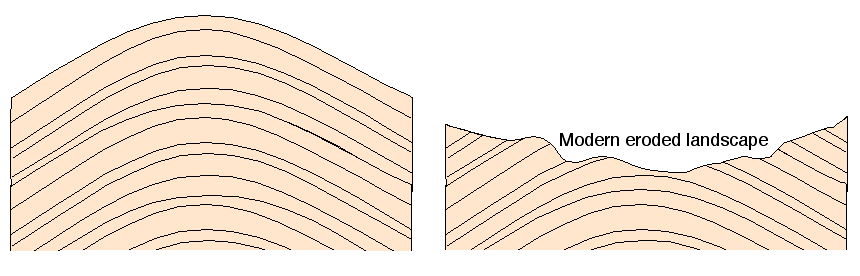

At this point, you may be saying "Hold on! An anticline is supposed to be an upward bump, and I'm seeing a huge depression here!". If so, you're right. After the anticline formed (after the layers of rock were folded), erosion cut down through the top. It reached relatively soft layers in the middle of the anticline and cut down even more there, leaving a valley in the middle of the anticline. See the sketches below.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This is what is called topographic inversion: the topography of the present land surface has the opposite trend of the shape of the rock layers. Where the layers go up, the land surface goes down. If that seems like an unfortunate complication, bear in mind that we probably couldn't see the anticline if the middle hadn't been cut away by erosion this process of topographic inversion.

|

|

|

|

Finally, let's move on to the view from Location 3. Now we're looking across the reservoir at the core of the anticline to the north.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

For the most part, we're seeing an anticline as we would expect it: an upward bend in layered rocks. You may be able to see the effects of a small fault in the left-center of the outcrop.

So who cares? From the standpoint of earth history, anticlines record serious compression of the Earth's crust and commonly develop during mountain-building events. That's true here: the Virgin Anticline is thought to have formed about 70 million years ago during an early phase of the building of the Rockies.

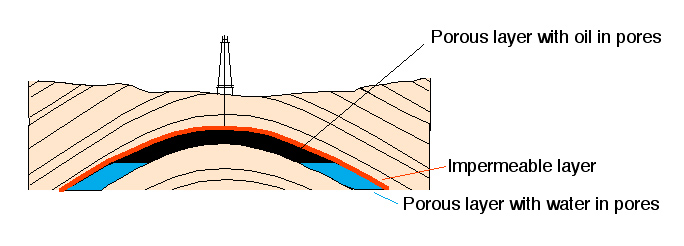

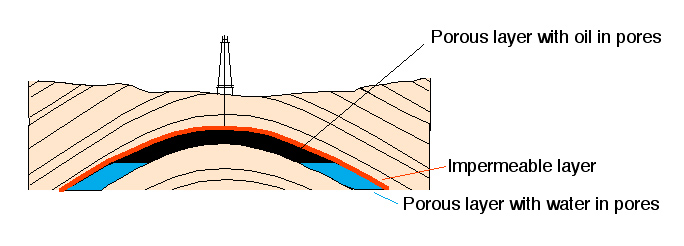

From a more pragmatic standpoint, anticlines commonly house large accumulations of petroleum. Oil moves upward through the earth because it's lighter than water, and so it commonly moves up through the limbs of anticlines via porous layers of sandstone. If the overlying layer of rock is impermeable, the oil stops in the crest of the anticline. The majority of the world's oil fields are developed in anticlinal traps. The Virgin Anticline has no oil in it as we see it here, but it provides a visible model for the source of much of the petroleum that we burn today.

|

|

|

|

|

|